AI Hurricane Forecasting, a new hammer in the toolbox for saving lives and property

By Theresa Barosh | Aug. 2025

Artificial Intelligence is like a shiny new tool, say a hammer. It may be tempting to start hitting every nail with the new hammer. However, it makes all the difference when a well-trained carpenter wields the hammer with expertise.

In the context of hurricanes, that means the person training a weather prediction AI needs to know a lot about severe weather. Otherwise, results can spiral way outside of the realm of possibility, like predicting over 400 mph hurricane winds, nearly twice that of the highest ever recorded one-minute sustained hurricane winds. Maximum sustained winds define the strength or intensity of a hurricane.

CIRA researcher Kate Musgrave specializes in AI hurricane forecasting. With family in the Southeastern United States, the challenge of hurricane forecasting is extremely important to her. “We want to bring every tool to the table. I mean, we’re talking about lives. We’re talking about property. We want to make sure that we are putting everything in front of the forecasters that can help improve the outcomes from these landfalls.”

Musgrave, alongside other CIRA research team members, evaluates AI weather prediction models. Led by Senior Research Scientist Mark DeMaria, the team found that while Al models tend to do well with detecting hurricanes and forecasting where one is likely to go, Al models often fall short when attempting to forecast the intensity of a hurricane. One of the exceptions to this finding is Google DeepMind’s AI-based tropical cyclone model.

The team supports NOAA’s National Weather Service forecasters and the National Hurricane Center. CIRA researchers have been working on statistical models for the National Hurricane Center for decades.

“Anywhere you’re applying statistical models, you could be applying artificial intelligence or machine learning models,” said Musgrave. Unlike traditional weather models, based on physical processes, machine learning uses probabilities – or statistics – to predict outcomes.

Using AI to make weather predictions requires a lot of historical data for the AI to train on and build probabilities. Musgrave said that provides a challenge, especially in the case of hurricanes.

“If you think about it, you’ve got local temperatures everywhere, every day,” said Musgrave, “We don’t have a hurricane everywhere, every day. They’re pretty rare. You’re only talking about up to a hundred globally every year. That’s not a huge number. When you’re trying to do statistical analysis, when you’re trying to do AI, they need thousands upon thousands of data points to train these models.”

Musgrave’s team helps connect AI models with forecasters.

“We do some development of our own, but we also are looking more broadly at how can we apply this to protect human life and property, and that’s through working with the National Hurricane Center and the Joint Typhoon Warning Center to improve their forecasts.”

Working at a cooperative institute, an agreement between NOAA and a university such as Colorado State University, provides a unique situation to support forecasters. “A large part of what is a cooperative institute is that we want to be that bridge to make sure that all of this great work that’s being done in the research community can actually be useful to the forecasters and to the public.”

Learning From the Past

“Back before we had the satellites, the only way that that people would get warnings about landfalls was if a ship happened to be unfortunate enough to go near one, but fortunate enough to survive.” said Musgrave. “Or if we got notices from one of the islands, ‘this one hit,’ and then you have a storm randomly in the Gulf that nobody knew where it was, where it was going to land or when.”

Hurricane forecasting is now supported through a myriad of resources, including weather satellites, AI weather models and hurricane hunters. The Cooperative Institute for Marine and Atmospheric Studies, based at the University of Miami, supports hurricane hunters who fly near or into tropical storms to get weather measurements. These flights collect information in real time, inside storms that satellites cannot provide.

In 1989, NOAA hurricane hunters flew into the eyewall of Hurricane Hugo with 185 mph peak horizontal winds. The aircrew found that the storm was much worse when they arrived than satellite estimates suggested when they had taken off. They went through a grueling experience, losing one of their four engines before escaping the storm with support from another aircraft.

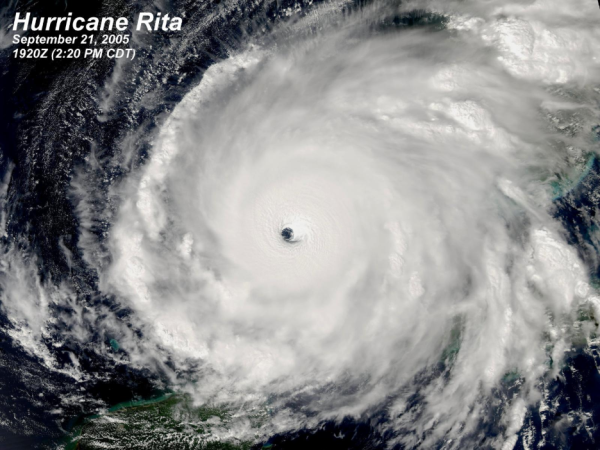

Satellite imagery and data have improved since, with new tools on each generation of satellites that go up. Weather satellites, a specialty at CIRA, are extremely important for hurricane prediction because most weather stations are on the ground rather than taking measurements over the ocean. Weather satellites allow for near-real time observations of the weather over oceans.

“Since about the late ‘80s, early ‘90s, CIRA has had a very strong tropical expertise resident with us both on the NOAA side and on our CIRA research staff,” said CIRA Director Steve Miller. “With the idea being that we can extract from the basic research about tropic systems certain things that can help us better predict what tropical storms are going to do next.”

CIRA’s team now includes multiple tropical storm experts, like Musgrave. A single satellite image includes a lot of information, so using satellite imagery when training weather AIs can be especially useful.

Hurricane Floyd provides an excellent example of why precise hurricane forecasting is important, said Musgrave. In 1999, Floyd led to evacuation orders for over 2.6 million coastal residents across five states. It made landfall as a Category 2 hurricane in North Carolina and traveled into New England, causing 85 deaths and an estimated $6.5 billion in damage.

About a month after Hurricane Katrina in 2005, Hurricane Rita threatened Houston. Over 100 people evacuating from the area died due to challenges of evacuation and the aftermath. Twenty-three nursing home residents died in a bus fire. Then, Hurricane Rita hit far east of Houston. Musgrave said this historical event emphasizes the need for accurate landfall forecasts so that only people who absolutely need to evacuate get the order.

Many Hurricane Rita fatalities came from heat exhaustion. Some residents, such as elderly and others who are sensitive to heat, need to prioritize access to air conditioning. Heat exhaustion continues to be a concern after a hurricane passes, particularly if infrastructure damage reduces access to air conditioning. Temperatures tend to climb in the wake of a hurricane – paired with raised humidity – increasing danger to residents.

CIRA’s work with hurricane satellite imagery has made tracking tropical storms in real time easier.

“We formulate new graphical tools, decision support tools,” said Miller, “That the National Hurricane Center can then use to better visualize, better communicate and advise the public on these most dangerous storms that we call hurricanes.”

As CIRA researchers work on training the next weather prediction AI focused on accurately predicting hurricane intensity, they look forward to a set of geostationary weather satellites scheduled to launch in the early 2030’s with new sensors and tools.

What is needed: Continued support for NOAA Cooperative Institutes, hurricane hunters, weather satellites and AI hurricane researchers because hurricane forecasters need the information and support to continue to save lives.